The subtitle is “The Gnostic Mass Movements of Our Time,” which nicely summarizes what he’s up to here. Voegelin’s thesis is that there are numerous modern political movements that in the structure of their belief systems resemble Gnosticism.

(Gnosticism was a religious movement in antiquity, existing at the same time as early Christianity, probably preceding it, and which exercised some influence early in the history of Christianity as a heresy.)

Voegelin gives six central characteristics of Gnostic belief structure:

- The Gnostic is “dissatisfied with his situation.”

- The cause of this dissatisfaction is attributed to the “intrinsically poor…organiz[ation]” of the world.

- It is believed that salvation for/from the corrupt, poorly organized world is possible.

- The method of transformation of the corrupt world for a perfect one will be historical and this-worldly.

- Human action can produce this beneficial transformation of the world.

- The Gnostic sees his task as acquiring the knowledge to transform the wicked world and then acting as a prophet of the need for this transformation.

Among the political movements Voegelin classifies as Gnostic in structure are progressivism, positivism, Marxism, psychoanalysis, communism, fascism, and national socialism. As I indicated in our discussion, I want to suggest that wokeism—a mutated and much more virulent form of progressivism that negates virtually every founding institution of Western civilization—should be included as the latest such movement.

The Gnostic perspective on the direction of the change desired is modeled on the Christian idea of perfection, though it necessarily distorts it in moving it from the supernatural realm to this world.

For the Christian, perfection is achieved by the justified believer only in the afterlife, though this life is sanctified as the training ground for efforts to reach that pure state.

For the Gnostic, it is envisioned that the perfect state can be reached in this world, whether that perfect state is only hinted at and the emphasis is on the progressive movement toward it or it is carefully defined, as in Marxism’s vision of a classless communist utopia to follow the fall of the bourgeoisie.

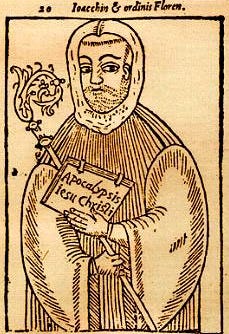

Voegelin then launches on an analysis of the symbolic structures at work in the thought of a 12th century Christian theologian Joachim of Fiore (below), in order to show how many of these modern political Gnosticisms borrow from that structure.

Joachim imposed the trinitarian nature of God on history, claiming that world history would consist of three great ages, that of the Father (from the beginning until Christ), that of the Son (from Christ until the mid-13th century), and that of the Holy Spirit (what came after that). Modern Gnostic movements borrow this tripartite symbolism: Marxism sees human history as divided into the era of primitive communism, the era of capitalism, and the era of classless utopia, whereas wokeism thinks in terms of a similar trinity of primitive freedom and equality (sub-Saharan Africa and the Americas before the arrival of the Europeans), slavery, and finally liberation in the perfect and hierarchy-free multicultural society.

Joachim also emphasized the importance of great leaders and prophetic figures that would be needed to move from one epoch to the next. The communist and fascist fascination with all-powerful leader figures (Lenin, Stalin, Mao, Castro, Mussolini, Hitler) and prophets (Marx, Trotsky, Gramsci), who are typically intellectuals, is structurally very similar.

Finally, Joachim believed “the community of spiritually autonomous persons…a community of monks” was the engine of movement through the stages. Their autonomy is centrally about freedom from institutions. In Joachim’s case, this meant mostly independence vis-à-vis the sacraments of the Church. For the neo-Gnostics, it often is seen as escape from the bonds of the state, the family, and all other social institutions.

The Gnostic program for perfecting the world must, in Voegelin’s argument, omit elements of the nature of the world and being that disprove the program. He demonstrates this by looking briefly at such omissions in the work of Thomas More, Hobbes, and Hegel.

The Gnostic project is a corruption of Christianity also in the ease by which it is believed. Christian faith, by contrast, requires great personal strength, given the paucity of “tangible” certainty to undergird it. The leap of faith is difficult and it is constantly challenged by empirical affairs.

Gnostic movements are thus tempting especially to those who lack “spiritual stamina”: “[G]reat masses of Christianized men who were not strong enough for the heroic adventure of faith became susceptible to ideas that could give them a greater degree of certainty about the meaning of their existence than faith.”